Because the philosophy of hedonism (explored here) colors the way we view the Gospel, it is often easy to assume that if we live righteously, the Gospel of Jesus Christ will insulate us from (or, at least, dramatically lessen) the pains and sorrows that come with mortal life — an assumption we here refer to as “the yellow brick road.”

The “yellow brick road” assumption can be contrasted with what we will call “the road through Gesthemane” view, a perspective which refers to the Savior’s infinite suffering on our behalf, the similar (but lesser) suffering and sorrow we inevitably experience on our path of Gospel living. The Gospel does not insulate us from the pains and sorrows of mortality, but rather changes how we can understand and experience such things.

The Hidden Worldview: The Yellow Brick Road

The Gospel inoculates us against pain and suffering.

In a previous installment, we discussed the philosophy of hedonism, or the belief that happiness is defined by positive emotional experiences and having such experiences is our highest goal in life. This assumption, which is quite widespread in our larger culture, can unfortunately lead many Latter-day Saints to believe that the Gospel of Jesus Christ is designed to take away pain and suffering in our lives, and that turning to Christ by obeying His commandments and living a life of righteousness will lead to a life of uninterrupted enjoyment and positive affect. We often (correctly) teach others that happiness and peace are fruits of Gospel living, but we sometimes go further and presume that all sorrow, suffering, and pain can be prevented or relieved through repentance and Gospel living.

Carlfred Broderick famously described a fireside that he presided over as a stake president for Primary girls who were making the transition into the Young Women’s program:

They had a lovely program. It was one of those fantastic, beautiful presentations—based on the Wizard of Oz, or a take-off on the Wizard of Oz, where Dorothy, an eleven-year-old girl, was coming down the yellow brick road together with the tin woodman, the cowardly lion, and the scarecrow. They were singing altered lyrics about the gospel. And Oz, which was one wall of the cultural hall, looked very much like the Los Angeles Temple. . . . There were no weeds on that road; there were no munchkins; there were no misplaced tiles; there was no wicked witch of the west. . . .

Following that beautiful presentation with all the snappy tunes and skipping and so on, came a sister who I swear was sent over from Hollywood central casting. . . . She looked as if she had come right off the cover of a fashion magazine—every hair in place—with a photogenic returned missionary husband who looked like he came out of central casting and two or three, or heaven knows how many, photogenic children, all of whom came out of central casting or Kleenex ads or whatever. She enthused over her temple marriage and how wonderful life was with her charming husband and her perfect children and that the young women too could look like her and have a husband like him and children like them if they would stick to the yellow brick road and live in Oz. It was a lovely, sort of tear-jerking, event.((Carlfred Broderick, “The Uses of Adversity,” available at: https://rusch.files.wordpress.com/2006/09/the-uses-of-adversity.pdf))

This implication here is that the Gospel provides us with a formula, or a lifestyle, that will allow us to sidestep all of the sorrows, suffering, and pain that others experience in this life. We offer the Gospel to those who suffer with the expectation that their troubles will be over if they would just accept Christ and His church. We describe “happiness” as the ultimate blessing of living every commandment. Because of the prevailing (though hidden) assumption of hedonism, we sometimes imagine that we are, by virtue of our goodness, entitled to a life relatively free of adversity — or, at least, a life free from any really big challenges, unfair setbacks, or deep sorrows. And so when suffering and grief come into our lives, we sometimes question our own righteousness, or, worse, question the Gospel of Christ and its promises.

Additionally, sometimes we can come to believe that having success, enjoying a life of ease and an absence of worry, and consistently experiencing positive emotions and things that make us happy is a sort of “proof” that we or others are living righteously and enjoying the fruits of obedience and the blessings of God. Even more insidiously, we can come to believe that those who are struggling, suffering setbacks and challenges, or who are experiencing emotional difficulties are in some way less faithful or obedient than we ourselves are. After all, we might say to ourselves, “God wants us to be happy, and happiness is all about positive feelings and experiences, and the surest way to to get such feelings and have such experiences is to be obedient and faithful. So, if that’s not happening, then faith and obedience must be lacking.”

The Alternative: The Road through Gethsemane

Living the Gospel can lead us through suffering, but changes how we experience it.

Christ does not offer us a Yellow Brick Road free of pain, sorrow, and suffering. A brief survey of the scriptures will quickly demonstrate that we can all but guarantee that suffering and sorrow is one of the prices of true discipleship. Indeed, as C. S. Lewis noted, “We were promised sufferings. They were part of the program. We were even told, ‘Blessed are they that mourn.’”((CS Lewis. Grief Observed. Zondervan, 2001.)) Elsewhere, he stated:

Talk to me about the truth of religion and I’ll listen gladly. Talk to me about the duty of religion and I’ll listen submissively. But don’t come talking to me about the consolations of religion or I shall suspect that you don’t understand.((CS Lewis. Grief Observed. Zondervan, 2001.))

Early Christians were persecuted and killed for their faith. The Latter-day Saint pioneers gave up their homes, families, and belongings to follow God’s prophet across the plains — only to lose even more family members (and sometimes their very lives) in the journey. Abinadi was murdered for teaching about Christ. Amulek, after converting to Christ, watched some of his former colleagues murder his convert friends and family because of their faith. And Paul stated that Moses chose “rather to suffer affliction with the people of God, than to enjoy the pleasures of sin for a season” (Heb. 11:25).

Furthermore, contrary to how we sometimes imagine it, life in the eternities is not a life of neverending positive emotions — sorrow and pain are not merely experiences reserved for our brief mortal lives. We understand from modern revelation that eternal life is the life that God lives — and God’s life is full of sorrow and heartache. Modern-day revelation tells us that Enoch reports that he saw the “God of heaven [look] upon the residue of the people, and he wept,” because of the love that He felt for them and because of His grief at their wickedness. Similarly, in the Book of Mormon we read that the resurrected Savior “groaned within himself, and said: Father, I am troubled because of the wickedness of the people of the house of Israel” (3 Ne. 17:14). As we become like our Father in Heaven, and live the life He lives, we can expect to step into similar sorrows and heartaches.

Remember that the Savior Jesus Christ Himself, who lived a sinless, perfect life, nonetheless suffered “temptations, and pain of body, hunger, thirst, and fatigue, even more than man can suffer, except it be unto death; for behold, blood [came] from every pore, so great [is] his anguish for the wickedness and the abominations of his people.” The idea that righteousness inoculates us against pain is not only of non-Christian origin (e.g., the philosophy of hedonism), it defies the basic tenets of the Christian faith. Elder Jeffrey R. Holland has insightfully observed:

I am convinced that [gospel living] is not easy because salvation is not a cheap experience. Salvation never was easy. We are The Church of Jesus Christ, this is the truth, and He is our Great Eternal Head. How could we believe that it would be easy for us when it was never, ever easy for Him? It seems to me that [each of us] have to spend at least a few moments in Gethsemane. [Each of us] have to take at least a step or two toward the summit of Calvary.

Now, please don’t misunderstand. I’m not talking about anything near what Christ experienced. That would be presumptuous and sacrilegious. But I believe that [each of us], to come to the truth, to come to salvation, to know something of this price that has been paid, will have to pay a token of that same price. …

If He could come forward in the night, kneel down, fall on His face, bleed from every pore, and cry, “Abba, Father (Papa), if this cup can pass, let it pass,” then little wonder that salvation is not a whimsical or easy thing for us. If you wonder if there isn’t an easier way, you should remember you are not the first one to ask that. Someone a lot great and a lot grander asked a long time ago if there wasn’t an easier way.((Jeffrey R. Holland, “Missionary Work and the Atonement.” Elder Holland was talking specifically about missionaries, but I felt it was safe to generalize his remarks to each of us in every aspect of our lives.))

When we follow Christ, we follow His footsteps into suffering and heartache. In short, life isn’t all about positive experiences. We will have negative experiences, whether we are following Christ or not. In fact, we can all but guarantee that suffering and sorrow is one of the prices of true discipleship. Psychologist and former BYU professor Brent Slife explains:

If Christ’s life reveals nothing else, it reveals that a Christian family is likely to experience suffering as well as happiness. (The book of Job describes another devoutly religious person who suffered considerably.) It is only the modernist “foundation” of hedonism that leads many to assume that a Christian family should experience mainly joy and happiness.((Slife, B. D. “Modern and postmodern value centers for the family.” In conference, “Disenchantments with Modernism,” Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. 1997.))

The doctrine of the Atonement teaches us that the highest good life has to offer is reconciliation with God — a peace we can experience even in the midst of psychological or emotional suffering. President Oaks explains that the liberating, healing, comforting power of the Atonement to “make us whole” may not always involved the immediate reduction of our pain:

Healing blessings come in many ways, each suited to our individual needs, as known to Him who loves us best. Sometimes a “healing” cures our illness or lifts our burden. But sometimes we are “healed” by being given strength or understanding or patience to bear the burdens placed upon us.

The people who followed Alma were in bondage to wicked oppressors. When they prayed for relief, the Lord told them He would deliver them eventually, but in the meantime He would ease their burdens “that even you cannot feel them upon your backs, even while you are in bondage; and this will I do that ye may stand as witnesses … that I, the Lord God, do visit my people in their afflictions” (Mosiah 24:14). In that case the people did not have their burdens removed, but the Lord strengthened them so that “they could bear up their burdens with ease, and they did submit cheerfully and with patience to all the will of the Lord” (v. 15).((Dallin H. Oaks, “He heals the heavy laden,” Ensign, November 2006.))

The Lord God will often visit the righteous in their afflictions, rather than straightaway remove their afflictions. In a previous installment, we explored how the scriptures define happiness: the presence of God in our lives. The abiding peace that ensues when we are made right with God and share His presence is the definition of happiness, it is peace and joy, and this can be experienced whether we are enjoying a pleasant and satisfying life or in the midst of the deepest sorrow and pain.

Negative and positive emotions can be experienced in different ways.

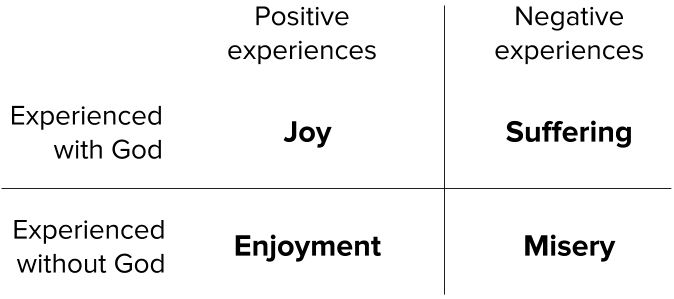

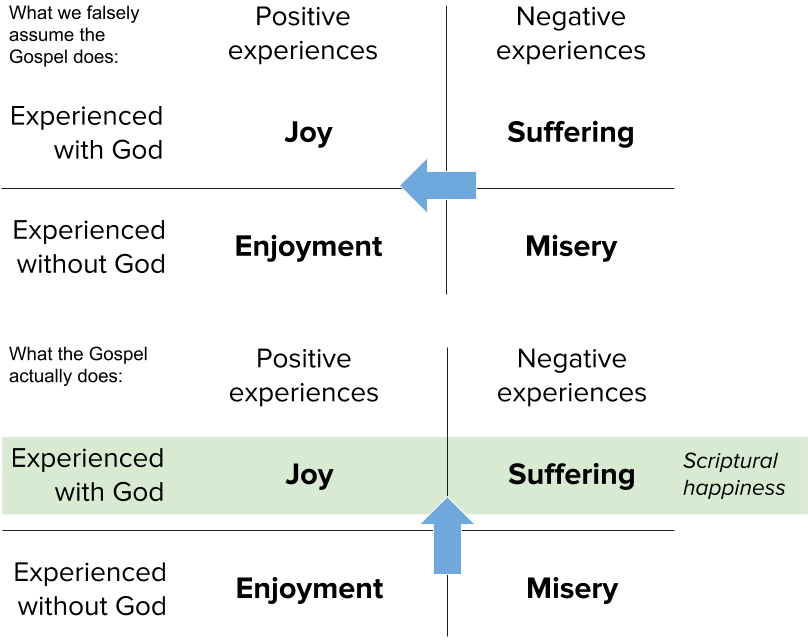

We would like to propose that there are two types of pain: (1) When experienced without God in our lives, negative experiences can be referred to as misery. (2) When experienced with God in our lives, negative experiences can be referred to as suffering. Both are equally negative experiences, but there is a qualitative difference in how we experience them. The same is true for positive experiences: We can experience excitement, thrill, cheer, satisfaction, and pleasure while at the same time having hearts at war with God. We can also experience those same positive emotional experiences while being one with God. Here, we refer to the former as enjoyment, and the latter as joy. (Note, these various labels do not always dovetail with how they are used in scripture, but merely serve as a convenient shorthand for the distinctions we are articulating in this article.) See the chart below for an illustration.

Consider the words of Christ, who said that those who don’t center their lives in His gospel “have joy in their works for a season,” but those who live that Gospel shall find eternal peace and joy. We argue that the difference is not just in the duration of the positive experience, but also in the quality of it as well. The joy of someone who experiences the presence of God is qualitatively different than the enjoyment of someone who is alienated from God. Similarly, the suffering of someone who is right with God is qualitatively different from the misery of someone who is at odds with God.

When our thoughts are centered on ourselves, we sometimes nurse feelings of self-pity in the midst of our suffering. This bitterness of soul is misery — a kind of misery that those who are reconciled with God do not experience, even though they too may endure the same negative experiences or may be wronged in the same way by others. Consider, for example, the Nephite people’s experience with adversity and war:

But behold, because of the exceedingly great length of the war between the Nephites and the Lamanites many had become hardened, because of the exceedingly great length of the war; and many were softened because of their afflictions, insomuch that they did humble themselves before God, even in the depth of humility. (Alma 62:41)

In these verses, we learn that there were two groups of Nephites, each of which responded differently to the grief, pain, and adversity of war. Some hardened their hearts and nursed a sense of resentment towards God and others in their pain. Others softened their hearts, and learned compassion towards others and humility before God. The emotional and psychological experience of these two groups was qualitatively different. The difference was not in degree of pain they felt, but the state of their hearts towards God and others while experiencing it.

As mentioned before, the “Yellow Brick Road syndrome” is the assumption that turning to Christ and living the Gospel will lead us to a life free of sorrow and pain. We assume that the Gospel of Jesus Christ turns negative experiences into positive experiences, or that it will take us out of the right hand column, and into the left hand column, of the chart above. We argue, however, that the Atonement and Gospel of Jesus Christ does not take us out of the left-hand column, but instead it takes us out of the bottom row. It doesn’t inoculate us against pain, it transforms our pain.

Dr. Arthur Henry King explains that as we reconcile ourselves with God through the Atonement, our thoughts and our hearts will turn towards others. He taught: “In the long run our greatest difficulty is to be humble enough to put ourselves in the position to be saved, a position that may mean losing the self-concern of the struggle within ourselves, and looking outward to be concerned with others and their struggles.”((Arthur Henry King, “Atonement: The Only Wholeness,” Ensign, April 1975.)) This puts a new spin on the scripture, “Men are that they might have joy” (2 Nephi 2:25). The word “joy” here does not mean “positive emotional experiences,” but rather the peace that comes from a heart free from self-concern.

Consider further—while righteous suffering might include physical pain or personal emotional heartache, it also includes sorrow and suffering on the behalf of others. Think about Christ, when he wept because of the death of Lazarus. God weeps because of the suffering and sins of those He loves. Think of the sorrow a mother feels for a lost child—that kind of sorrow is certainly a Godly sorrow, born of love, compassion, heartache, and bereavement. None of these are the same as misery, which could accompany grief and bereavement without the comfort of the Gospel, or which is full of self-concern.

In conclusion, the relationship between the Gospel of Jesus Christ and suffering can be succinctly summarized by Broderick’s remarks to the young women after the presentation he described above: “The gospel of Jesus Christ is not insurance against pain. It is a resource in the event of pain, and when that pain comes (and it will come because we came here on earth to have pain among other things), when it comes, rejoice that you have resource to deal with your pain.” Living the Gospel certainly helps us avoid some of the unique heartaches that result from sinful living. But we should be cautious not to imply that the Gospel shields us from pain, and explore instead how the Gospel can be a resource in the event of pain.

I love this concept and especially your image,

Encouraging people to indulge in short term pleasure or “enjoyment” to use your phrase, at the expense of long term temporal and spiritual misery is a tremendous diservice.

However, we must be wary and not perniciously apply the application that it is ours to cause and allow suffering amongst others than to alleviate it.

I’ve known of those exercising unrighteous dominion who thought it was their job to make things more difficult for people literally just for the sake of adding burdens and difficulties in guise of helping them grow by doing hard things, as if mortality does not have enough trials built in, and living a live of discipleship having enough to give people opportunities to learn and grow by serving others.