- Introduction

- What If Truth Is a Person?

- The Ancient Roots of Person Truth

- Faith in ideas, or faithfulness to a Person?

- Knowing God vs. believing ideas about Him

- Person-truth does not give us control

- Knowing Person-truth through covenant

- Our on-and-off relationship with Person-truth

- The arch-nemesis of Person-truth

- What it means to be an authority on truth

- What is sin, if truth is a Person?

- Rethinking the Atonement of Christ

- Person-truth in an age of science and reason

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Further Readings

- Appendix B: More on Greek and Hebrew thought

- Appendix C: Questions and answers

How we think about truth (and how we think about sin) influences how we think about Christ’s sacrifice for us. We feel it necessary, however, to begin this this chapter with an important caveat from C.S. Lewis:

We are told that Christ was killed for us, that His death has washed out our sins, and that by dying He disabled death itself. … Any theories we build up as to how Christ’s death did all this are, in my view, quite secondary: mere plans or diagrams to be left alone if they do not help us, and, even if they do help us, not to be confused with the thing itself.((C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (1952; Harper Collins: 2001), 54-56.))

Every committed Christian accepts that Christ’s death can save us. But there are many different theories about how this happens, and why Christ’s death was necessary. The scriptures do not give technical explanations of the Atonement. Rather, they use metaphors instead. They compare sin and forgiveness to birth, food, medicine, money, lost livestock, marriage, government, and other things. These metaphors each reveal important insights into the Atonement, and each potentially conceals important insights as well.

One of the more common conceptions of the Atonement is commonly called the Penal-Substitution theory of the Atonement.((See, Thomas R. Schreiner, “Penal Substitution View,” in The Nature of the Atonement: Four Views, ed. James Beilby and Paul R. Eddy (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006), 67-116.)) The essence of the penal-substitution theory is, as C.S. Lewis succinctly states it, “being let off because Christ has volunteered to bear a punishment instead of us.”((C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (1952; Harper Collins: 2001), p. 56.)) This view assumes that sin is the violation of an abstract moral law. This abstract moral law requires that a penalty be exacted for sin, typically in the form of personal suffering (such as the fiery damnation of hell, or an afflicted conscience).

From this view, God is a preeminent legal scholar and well-versed in cosmic law. He sees a loophole that allows Him to save His sinning children: vicarious punishment. It will only work if the punishment is voluntarily accepted by one who has not also violated the law (such as the sinless Christ). On this view, because Jesus was perfectly sinless, He could stand as a worthy substitute for us. In suffering on our behalf a punishment that He does not deserve—but which we most certainly do—He is able to satisfy the demands of cosmic Justice.

If we meet the new conditions that God and His Son now set for us, it becomes possible for us to escape damnation and be “let off the hook,” so to speak. The new conditions are much more generous, since Christ can exercise much more discretion than the inflexible demands of universal law. In this way, God can extend to us Mercy while satisfying Justice, and be simultaneously both Just and Merciful. This view of the Atonement draws heavily from the idea view of truth, because it conceptualizes sin as the violation of the abstract law. It treats Christ’s death and suffering as required by that same law (which God cannot override).

Person-truth and the Atonement

If we understand sin a way of living that alienates us from God, rather than as a violation of immutable, abstract law, this can change how we think of the Atonement. The atoning sacrifice of Jesus Christ becomes an effort to reconcile us to God after we have estranged ourselves from Him. From this view, Christ’s mission is to repair our damaged relationship with God (rather than to appease the demands of some abstract Justice).

We can imagine God as a patient, compassionate Father who, when wronged, does not harbor resentment. Rather, He initiates the process of reconciliation. Through His divine Son, He condescends to our mortal state (1 Nephi 11:16-33), where He suffers with us when we suffer, mourns with us when we mourn, experiences everything we experience:

And he shall go forth, suffering pains and afflictions and temptations of every kind; and this that the word might be fulfilled which saith he will take upon him the pains and the sicknesses of his people. And he will take upon him death, that he may loose the bands of death which bind his people; and he will take upon him their infirmities, that his bowels may be filled with mercy, according to the flesh, that he may know according to the flesh how to succor his people according to their infirmities. (Alma 7:11-12)

The term used here is “to succor.” This word is derived from the Latin term “succurrere,” which means “to run to the rescue of another, or to bring aid.” In atoning for us Christ hurries to our side, selflessly sharing our infirmities so that He might be “filled with compassion” (see, e.g., Mos. 15:9; 3 Ne. 17:6; D&C 101:9). Indeed, the word “compassion” literally means “to suffer with another.” Through it all, He invites us to end our proud and stubborn rebellion and enter into a repaired and renewed relationship with Him.

To live out the Atonement—that is, to become “at-one” with God—requires that we respond to this invitation and loving condescension. As the prophet Jacob wrote, “Wherefore, beloved brethren, be reconciled unto him through the atonement of Christ” (Jacob 4:11). When we soften our hearts and accept this invitation to reconcile, Christ helps us become the kinds of beings that enjoy a deep relationship with God. If we have been mistreating our family, reconciling with them involves change. In a similar way, for Christ to reconcile us with God, we must change as people.

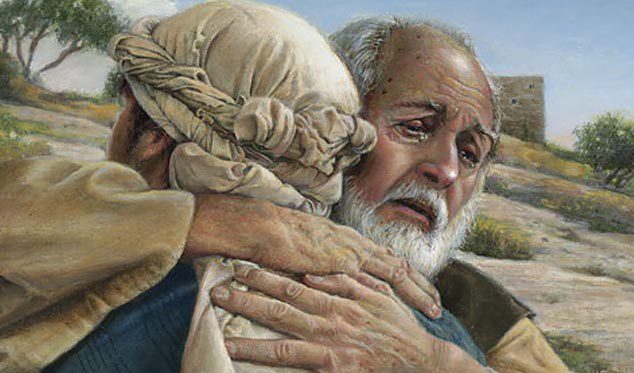

We have written a parable to help illustrate this view of the Atonement. Imagine that a son steals several items from his neighbors and his own parents to feed a drug habit. He leaves home, evades the police, and sinks deeper into the destructive lifestyle of the addict. Because of fear, shame, or resentment, he refuses to go home, and ends up in a homeless shelter. In a conventional account of the Atonement, the father could clear the son’s record only by serving the son’s jail sentence for him and paying the son’s debts to the neighbors. However, this would not address the son’s relationship-damaging habits and stubborn, prideful heart.

Imagine the father showed up at the homeless shelter with a sleeping bag and, to his son’s great surprise, said, “Hi there, Tommy. I’ve missed you so much. I can’t bear for you to be away and suffering like this anymore, so I’m moving in with you.” The son may protest, and feel remorse that he has brought his father to dwell in such a humble setting. Nonetheless, the father insists that he that, from now on, he will share evening meals with him, sleep in an adjacent cot, and just be with him until he is ready to come back home, where the rest of the family prayerfully awaits.

Of course, the boy must change his priorities and habits before he can truly restore his relationship with his family. The father cannot make his son’s changes for him. But he can remove every obstacle and excuse, and lovingly walk with him through the process. This loving condescension and grace initiates reconciliation and change, and breaks down whatever walls of pride and resentment the son has placed between him and his parents. Without the father reaching out and humiliating himself with his son, those walls of pride and resentment could grow until they became impenetrable.

In this view, the Atonement plays out less like a cosmic court hearing, and much more like an ongoing, earnest conversation between two friends or family members. God is whole-heartedly inviting mankind to change their ways so that broken relationships can be mended and damaged souls made whole. In a signal of sincerity, our reconciling God has subjected Himself to immeasurable suffering on behalf of His troubled children, to awaken within us a hope for reunion and desire for reconciliation, without which, we would be lost. In this way, the atoning work of Jesus Christ is an ongoing process rather than a single (historical) event, and it involves the Savior coming to us (the condescension of God) at least as much as us coming to Him.

In part because of the penal-substitution theory and other such legalistic theories of the atonement, it can be easy to think of repentance as being about punishment (or avoiding punishment). However, the person view of truth offer a different perspective. As Elder Theodore M. Burton has taught:

The Old Testament was originally written in Hebrew, and the word used in it to refer to the concept of repentance is shube. We can better understand what shube means by reading a passage from Ezekiel and inserting the word shube, along with its English translation. To the “watchmen” appointed to warn Israel, the Lord says:

“When I say unto the wicked, O wicked man, thou shalt surely die; if thou dost not speak to warn the wicked from his way, that wicked man shall die in his iniquity; but his blood will I require at thine hand. Nevertheless, if thou warn the wicked of his way to turn from [shube] it; if he do not turn from [shube] his way, he shall die in his iniquity; but thou hast delivered thy soul. … Say unto them, As I live, saith the Lord God, I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked; but that the wicked turn from [shube] his way and live.” (Ezek. 33:8–11)

I know of no kinder, sweeter passage in the Old Testament than those beautiful lines. In reading them, can you think of a kind, wise, gentle, loving Father in Heaven pleading with you to shube, or turn back to him—to leave unhappiness, sorrow, regret, and despair behind and turn back to your Father’s family, where you can find happiness, joy, and acceptance among his other children?

That is the message of the Old Testament. Prophet after prophet writes of shube—that turning back to the Lord, where we can be received with joy and rejoicing. The Old Testament teaches time and again that we must turn from evil and do instead that which is noble and good. This means that we must not only change our ways, we must change our very thoughts, which control our actions.((Elder Theodore M. Burton, “The Meaning of Repentance,” Ensign, August, 1988, 6-9.))

Seen in this way, repentance is a process of turning away from one thing and towards another. It involves leaving aside one way living and stepping into a new way of being—and doing so at the patient, persistent, loving invitation of a Heavenly Father who seeks only the eternal happiness of His children. When we turn away from sin, we cease betraying our covenants and reconcile ourselves with God.